ship-it - a humble script for low-risk deployment

Software teams like shipping software. We like doing it fast, and doing it well. We like to avoid making mistakes when doing so — especially costly or time-consuming ones. My team wanted to optimize for these values with automated feedback mechanisms in place.

Enter: ship-it — a script developed by my team1 to help us deploy better software faster, and get quicker feedback when things went wrong. Read on to find out what it is, what motivated its creation, and how those ideas could help you, too.

Deployment Process

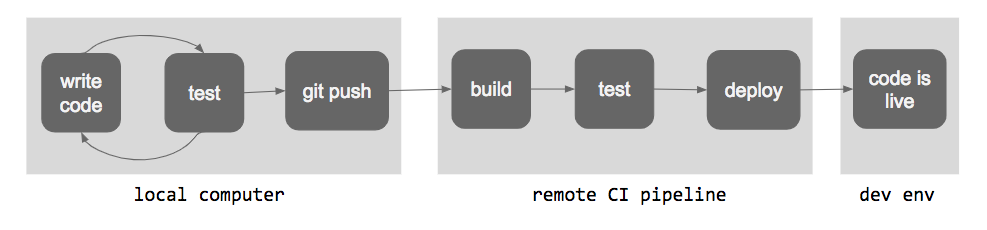

First, a bit of background about why the idea of low-risk deployment practices were important to us. Our development team worked with a pipeline that looked something like this:

We write tests and write code and run tests in a loop on our local computer. When we’re satisfied that a feature is completed, we do a git push to merge it into our main or develop branch. From there, a remote continuous integration (CI) system (such as Jenkins, TravisCI, CircleCI, GitLab, etc…) kicks in. It builds our code and runs our entire test suite in its own environment, clean and isolated from our local development system. If that’s green and passing, it will do a deploy to a live dev environment, where the feature can be tested and accepted by our PMs.

Of course, there are more steps, further to the right of this diagram. We’ll often have a QA or staging environment, and a production environment further down the pipeline. However, I don’t even want to get into those, because what I’m talking about today are the places where this pipeline fails . — and detecting those failures. And if you’re detecting them all the way over to the right, in prod, that’s not great.

In fact, I would argue that the further to the left of the diagram you find out about a failure, the better. It’s better to catch bugs in dev than it is in prod. It’s better to catch bugs in CI than it is in dev. And even better than catching bugs in CI is catching them on your local machine, before they ever get merged into the main branch.

Unfortunately, maybe you’re like me, and you’re a forgetful person. You’re heads-down, working on a feature, and you don’t remember… did I actually run all the unit tests one final time before I pushed, after I made that one small tweak that definitely wouldn’t break any tests? Did I remember to run the entire test suite before pushing, as I was running individually target unit tests along the way, only executing the pieces relevant to the code I was changing?

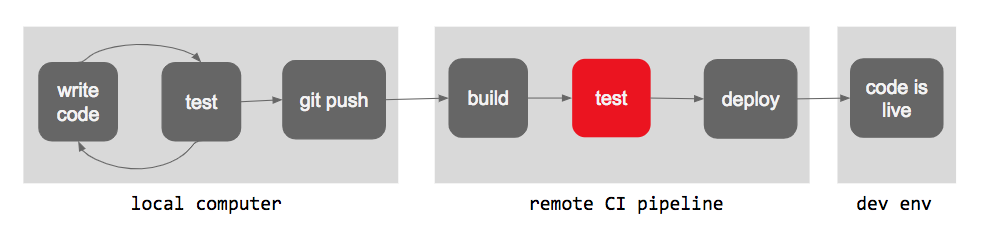

Often, the answer to these questions is “no”, and someone winds up pushing broken code to main. That’s fine! That’s why we have CI. So often, our pipeline diagram would look something like this:

When CI came back red, we would go back, and dive into the logs to figure out what went wrong. We’d identify the problem, fix the code, and push the fix. Problem solved.

So our CI board was commonly red. Sure, it always made it to green eventually. And sure, it meant that our bugs weren’t making it to the dev environment. But it meant slower feedback loops for the dev team, and a clogged pipeline, and an unclean commit tree.

Every time a bug failed in CI instead of on our local machine, we were waiting an addition 5–8 minutes to find out that something had gone wrong. And when it did, we had to go through CI logs, which are less user-friendly than local unit test output, in terms of identifying the exact cause of a problem. When a commit made the CI red, it was also blocking all other team members from pushing code, because our bug would break their commit as well. And it was frustrating to have our main branch scattered with commit messages for one-line fixes to small problems that we should have caught earlier.

We wanted those fast feedback loops. We wanted to smooth development. We wanted clean commit logs. What to do?

Enter: ship-it 🚢

ship-it, as the title of this blog has given away, is a script. And we’ll get into what exactly was in that script in just a moment. But more importantly, ship-it is a new team habit.

We removed the concept of git push from our vocabulary. It just wasn’t a thing we did anymore. Instead, it was always ./ship-it.sh.

And what was in ship-it.sh, exactly? Well, in its first iteration, it was pretty simple. Here’s 🚢 v1:2

#!/bin/bash

./runUnitTests.sh && git push

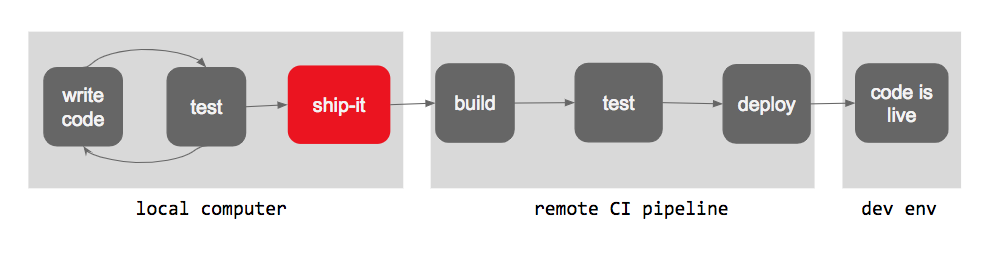

Thanks to this — the combination of the team habit, and the script itself — suddenly the view of our deploy pipeline changed:

ship-it would fail on our local computer, and catch any unit test failures before the commit got pushed. Faster feedback loops! Cleaner commit trees! Incredible! We’re done, right?

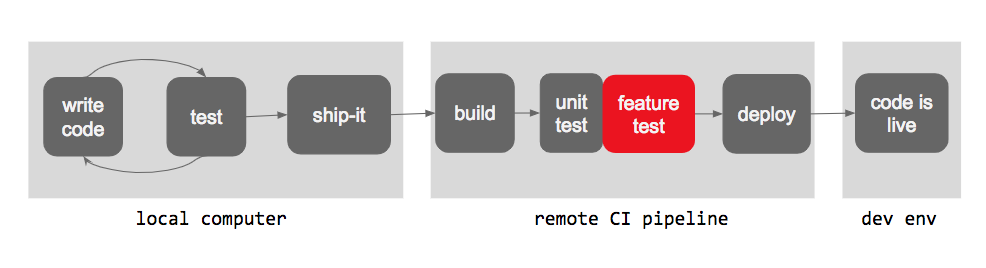

Well… not so fast. This pipeline illustration is, of course, oversimplified. There’s more to each step than the one-word descriptor shown above.

Specifically, I want to call out the box labelled “test” in the CI stage of the process. It just says “test” here, but to be more specific, the “test” stage of our CI pipeline had two steps involved: it ran our entire unit test suite, and it also ran end-to-end feature tests.

So, with the addition of the ship-it script shown above, we were catching the unit test failures locally. But not feature tests!

Of course, this necessitated an update to ship-it. Enter 🚢 v2:

#!/bin/bash

./runUnitTests.sh && ./runFeatureTests.sh && git push

From there, the metaphorical floodgates opened. We started thinking about all the other things we could catch locally, before we ever merged our code into main.

ship-it evolved organically, each iteration adding a unique piece of functionality as we had more ideas for how to make our deployment process cleaner and quicker.

🚢 ship-it now

Now, ship-it has grown into an exciting behemoth of a script that performs a lot of useful actions for our team. Here’s an outline:

- Before anything else,

ship-itclones the git repository into a brand-newprojectName-tmprepo, elsewhere on the machine. By doing this, it allows the script to build and execute the code in isolation, exactly as it is at the current state in the commit tree. This way, we can start on coding a new feature, without worrying that the changes will causeship-itto fail. - Next, it checks through our code for various stylistic anti-patterns. These were things important to our team in our codebase.

ship-itfailed out on: linting errors, any comments it detected in the code, or any “WIP” commit messages in our commit tree, or any time our circular-dependency checker failed. - If all that was okay, it ran our entire unit test suite. It would fail if any of the tests had errors or failures, and also if they printed any warnings. No more React missing “key” prop warnings for us!

- Next, it ran our end-to-end feature tests. For us, this required both our frontend and backend apps to be running on separate ports.

ship-itis responsible for spinning up both applications as part of execution, on separate ports than the ones we usually keep them running on with our dev server. When it finishes test execution, it’s responsible for killing those processes. - Finally, if all that works, it

git pushes our code! Our script printed a big ASCII-art happy face when it finished to let us know everything was all good:

´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶……..

´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´¶¶´´´´´´´´´´¶¶……

´´´´´´¶¶¶¶¶´´´´´´´¶¶´´´´´´´´´´´´´´¶¶……….

´´´´´¶´´´´´¶´´´´¶¶´´´´´¶¶´´´´¶¶´´´´´¶¶…………..

´´´´´¶´´´´´¶´´´¶¶´´´´´´¶¶´´´´¶¶´´´´´´´¶¶…..

´´´´´¶´´´´¶´´¶¶´´´´´´´´¶¶´´´´¶¶´´´´´´´´¶¶…..

´´´´´´¶´´´¶´´´¶´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´¶¶….

´´´´¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´¶¶….

´´´¶´´´´´´´´´´´´¶´¶¶´´´´´´´´´´´´´¶¶´´´´´¶¶….

´´¶¶´´´´´´´´´´´´¶´´¶¶´´´´´´´´´´´´¶¶´´´´´¶¶….

´¶¶´´´¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶´´´´¶¶´´´´´´´´¶¶´´´´´´´¶¶…

´¶´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´¶´´´´´¶¶¶¶¶¶¶´´´´´´´´´¶¶….

´¶¶´´´´´´´´´´´´´´¶´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´¶¶…..

´´¶´´´¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´¶¶….

´´¶¶´´´´´´´´´´´¶´´¶¶´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´¶¶….

´´´¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶´´´´´¶¶´´´´´´´´´´´´¶¶…..

´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶…….

Upsides and Downsides

Having ship-it as a part of our deployment pipeline really helped reduce the risk of all of our code pushes. It was a built-in tester, linter, style-checker, and validator that kept us all on our toes, and kept our commit tree clean and our CI board green.

Of course, there are a couple downsides to this whole process I want to call out:

1. ship-it is written in bash

Given the humble beginnings of ship-it detailed above, this made the most sense at the time. It was a lean experiment to make sure we were always running tests. But as ship-it grew naturally and organically, it continued to be written in bash.

But now, it has a lot of if-statements, and paths and error handling. It’s quite a long and tedious bash script, which makes it hard to understand and harder to edit. If we were to go back and write it again, we would probably pick a more readable language that makes scripting easy, like Python.

2. ship-it takes a long time to run

The longer it takes to run, the more time before we actually get the feedback we were optimizing for in the first place. This is why we added Step 1, where the script executes in an independent repository. It was taking long enough that we didn’t want to sit there waiting for it to finish. We wanted to keep writing code!

So for this important caveat, I think it’s important for any team implementing their own ship-it to consider what functionality is most important to them, and what isn’t, to keep the script as lean and fast as possible.

FAQ: Why not git hooks?

This is a common question we get — why go through the effort of having a script that runs and pushes for you? Why not use git hooks instead to have it happen automatically?

Well, that’s totally up to you, really. But here’s some of the reasons we preferred rolling our own ship-it over git hooks:

- We don’t want

ship-itscripts to be applied to branches. Generally, we do feature work on a branch, which often gets pushed with a “WIP” commit when the feature takes more than one day to complete. In these cases, our WIPs would likely have failing tests, console logs, and all the thingsship-itwould flag. Sure, you can add some logic to your hook scripts to prevent this. But at that point, with that added complexity,ship-itis way simpler. - Git hooks tightly couple your team and your development process to git. In

ship-it, it doesn’t matter if the final step is git push or svn commit or anything else. - You can’t test if your git hook is working without doing a commit or a push and confirming that things happen.

- Doing it yourself gives you full control over customization! For example, it would have been much harder to land on some of the cooler, more out-there

ship-itfunctionality if we’d just written a pre-commit hook to run tests for us.

🚢 ship-it and you

Right now, we don’t have an open-source version of ship-it available to share (but stay tuned!)

However, if your team was to write your own ship-it, perhaps starting with v1 or v2 and iterating for yourself from there, there’s a few questions I would recommend asking yourself to get you started.

Where does my code tend to fail, and how could I detect those failures earlier?

For us, this was a driving force between several of the additions we made it ship-it. My favorite example is the story of window.setSize().

Our feature tests were consistently failing in CI, after they had successfully passed ship-it locally. It was frustrating, flaky, and difficult to debug, since the CI runner was running the tests on a Windows VM it was spinning up in order to run the tests on IE10. And it didn’t know how to preserve the logs very well after running. 😱

It took hours of debugging and banging our heads against our machines, our CI runner, and our Windows VM before we figured out the cause. For whatever reason, the feature tests on Windows in CI were being run on a much smaller browser window size than what we were running with ship-it, which had the advantage of executing on our wide ultra-HD retina Mac displays.

Thanks to the smaller browser size, some of our buttons were getting moved around on the screen. Elements were hiding other elements, and the feature tests were failing.

After we made that discovery, we wanted to prevent that from happening again in the future. There was no way to increase the runner’s window size, so instead, we modified ship-it.

By adding a window.setSize() line to the part of ship-it that executed our feature tests, we forced ship-it to run under the same conditions as CI. And now, whenever we ran into an issue with window size, it was failing on our local machines, not on CI with its indecipherable log messages.

What annoying mistakes always accidentally make their way onto the main branch?

This is a straight-forward one, but a question that drove a lot of the functionality in ship-it that made us the happiest.

You know how, no matter how hard you try, you always end up accidentally committing a piece of code that you never intended to let slip?

Things like

console.log("does this work?")

or…

// TODO: delete this later

Letting our ship-it script flag all these and prevent us from pushing ended up being great for our team. It’s always so frustrating to admit defeat, and write that commit message that simply says “remove stray comment” or something along those lines. With ship-it, we kept our main branch as clean as possible. As more people joined our team and started working in the codebase, this became even more important, because it kept the style consistent and the code clean.

What’s next?

Right now, unfortunately, ship-it is not open-sourced, and I can’t provide the source code of the script we wrote. However, we’re interested in working on a project to re-create ship-it, open-source, in Python. We think that this will make it more widely accessible.

Until then, I would encourage teams to try out their own ship-it and see how it can grow and change with their own team needs as well! Experiment, iterate, and see what makes the most sense for your team and your context. And, of course, share the results! 😃

Externally published on Medium

Specifically, shoutout to Walter Scarborough for pairing on the development of ideas presented here! ↩

↩./runUnitTests.shis an abstraction here — for us it wasyarn testand./gradlew test, but the idea is not specific to those systems